Explaining concepts with the help of tactile images

This chapter introduces you to the world of concept development of blind children, including understanding the relation between the 3D world and its representation as 2D drawings. Meanwhile you will also learn a lot about children’s perception of the world. Part two of the chapter explains how the language of tactile images, a foreign language for children born blind, can be learned.

Concept development

Children begin preconceptual thinking between the ages of 2 and 3, forming subjective and often inaccurate precursors to true concepts. They make simple, visually based associations and struggle with broader categories, leading to over-generalization or over-discrimination. Around the age of 4, they develop true concepts by understanding shared features and actions.

Children with visual impairments develop concepts through multisensory experiences rather than sight alone, as descriptions alone may lead to incomplete or incorrect mental representations. Without direct interaction, they may form logical but inaccurate ideas, like imagining a bird sits on a branch like a human. Sighted children naturally explore through visual cues, while visually impaired children need targeted support to build concrete concepts such as a bird or a tree and abstract concepts such as spatial awareness, estimate distances, etc.

Children with visual impairments lack the visual stimuli that naturally activate and engage sighted children. As a result, they do not intuitively develop certain skills, such as orientation, distance estimation and speed judgment. Their concept development is more dependent on external guidance, emphasizing the importance of hands-on experiences and compensatory strategies to help them grasp their environment and broaden their understanding.

Young children with visual impairments have a limited understanding of many concepts, for example big animals. Sighted children learn through images and videos, while blind children may rely on a single tactile experience, like a toy elephant, making concept development harder. Some things can be heard, smelled and/or tasted but you cannot touch or feel lots of things that are too far, too dangerous, too small, etc. Some things are simply not in your environment, but in books or on screens, but what is an image for children with low vision? How do you ‘read’ an image?

A tactile image as a foreign language

A tactile image is, in essence, a concept of its own. Blind children need to learn and grasp the concept of an illustration before we can use tactile images to explain various concepts, for example: birds sitting on a branch. As any foreign language, the language of tactile graphics must be introduced step-by-step. However, simply making an image tactile does not guarantee that it will be meaningful or understandable. This challenge arises from the significant conceptual gap between 3D objects and their 2D representations in drawings.

Two types of books: Collage type illustrations and raised line drawings

Collage-type books use real objects and distinct materials to create tactile illustrations, making them easier for visually impaired children to recognize and interact with. Movable parts enhance engagement, allowing children to explore familiar elements like eyes, ears, or interactive story features (for example ‘a long journey’).

In contrast, raised line drawings rely on abstract shapes, lines, and textures, requiring interpretation and prior knowledge. While these drawings help introduce 2D concepts, they are essential for subjects like geometry and geography, making complex objects accessible. Both formats play a crucial role in education, bridging the gap between the tactile world and abstract representation (for example ‘Roundy’).

Learning to read tactile images

First, children explore lines and basic shapes by feeling and matching them with objects, learning that lines can represent different things. Playful activities help develop spatial awareness.

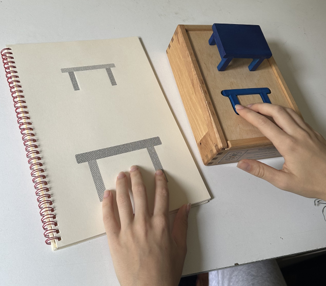

Next, the transition from 3D to 2D by using flat objects like hand outlines or a leaf. Matching these objects with their outlines gives the child immediate access to both – an object and its representation as a drawing. Tools like the Transfograph or 2½-D shapes help them connect real objects to their tactile representations. Whenever possible, children should be encouraged to make their own drawings. The more opportunities children have to create drawings, the better they become at reading and interpreting new drawings.

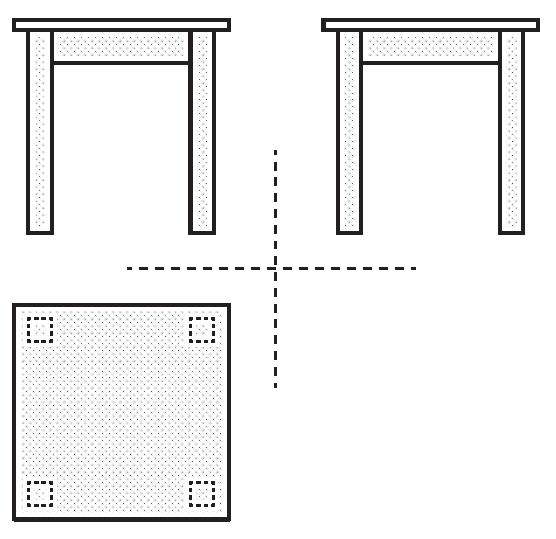

As concepts become more complex, children learn about perspective and overlapping through step-by-step exploration. Interactive tools like Fleximan help them understand body postures, movement, and abstract ideas like size and depth. Finally, children can learn to work with orthogonal projection, using a top, front and side view, all under right angles. Using this type of tactile graphic when describing a 3D-object, helps them to build a correct and precise mental representation