Introduction

Tactile books open the door to stories, concepts, and creativity, specifically tailored to visually impaired (VI) and blind children. Through the sense of touch, these books provide access to ideas, and information, helping children build mental representations of the world around them. Tactile books foster early literacy skills, allowing children to engage with narratives in a way that supports their understanding of language, spatial relationships, and abstract concepts. By exploring tactile images and textures, children can connect physical experiences with cognitive development, laying a strong foundation for future learning and comprehension. These guidelines address several key aspects of tactile book creation, including who these guidelines are aimed at, what tactile books are, why they are important, and how they are developed.

About the guidelines

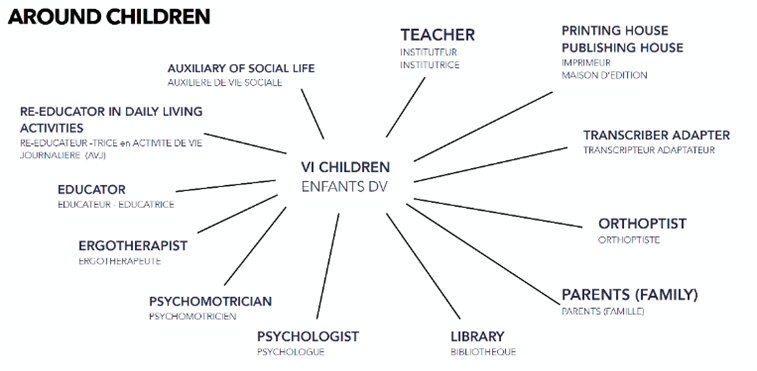

The guidelines are designed for various audiences, including parents, teachers, printing houses, designers, and anyone involved in creating or using tactile books for children. They offer a detailed explanation of what tactile books are, covering different types for different age groups and cognitive abilities. The importance of tactile books in promoting literacy and concept formation is also emphasized, with attention to their unique role in helping children form mental representations and understand complex ideas through touch.

Specifics about tactile illustrations and graphics are covered in depth, including guidelines on how to design and produce them, as well as an overview of techniques and materials suitable for different users. There is also guidance on where tactile books can be found, when they are typically used (at home or in schools), and why clear explanations and instructions for their use are crucial.

In the guidelines, you will find detailed advice on developing tactile books, from brainstorming story ideas to designing tactile images. It provides practical tips for different audiences involved in the process, from printing houses and designers to parents and teachers, highlighting the techniques and materials best suited for various contexts.

Notes for reading the guidelines

One important note is that the chapters have been written by different experts with varying levels of experience and English language skills. As a result, you may notice differences in writing style across chapters. Additionally, terminology such as “VI,” “BVI,” “tactile image,” and others may vary. While we have chosen not to standardize all terms, a glossary and appendix are included for clarification.

One of the central ideas of these guidelines is that that everyone involved in tactile literacy—whether it’s the parent, teacher, specialist, or child—should understand the underlying principles of tactile imagery, ensuring they “speak” the same tactile image language.